Attachment Styles

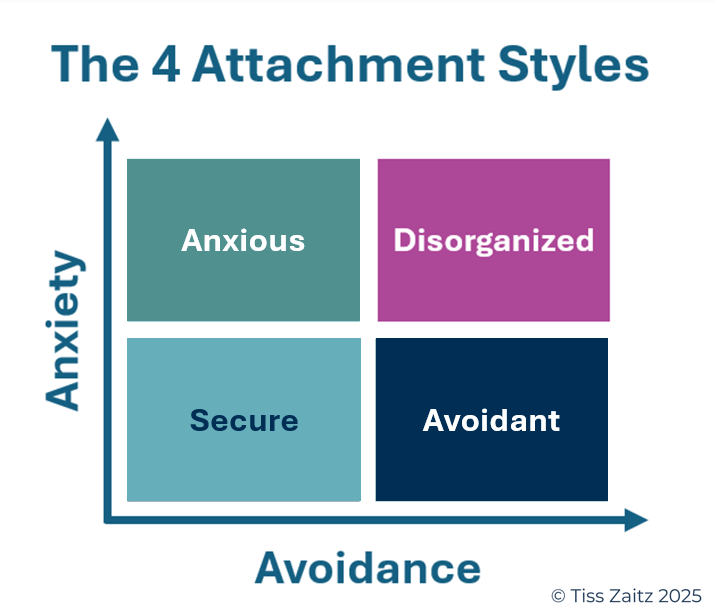

Attachment theory explains how early relationships shape how we connect, trust, and respond to closeness. It’s why some of us feel calm in relationships while others feel like they’re on an emotional roller coaster. These patterns, called attachment styles, fall along two dimensions: how much we fear rejection (anxiety) and how much we avoid closeness (avoidance). They’re not fixed traits we’re stuck with for life, more like unconscious strategies for how we manage relationships.

Secure: Low anxiety, low avoidance — comfortable with both closeness and space

Anxious: High anxiety, low avoidance — craves closeness but fears being forgotten

Avoidant: Low anxiety, high avoidance — values independence and avoids vulnerability

Disorganized: High anxiety, high avoidance — wants connection but being in it can feel unsafe

Secure Attachment

Someone low in both anxiety and avoidance has a secure attachment strategy. They feel safe with closeness and connection and trust that love doesn’t disappear with distance. They can express their needs and set boundaries.

Securely attached people don’t panic when things feel off or shut down when emotions run high. They’re not perfect or immune to insecurity, but their relationships are rooted in trust, not fear. They can stay connected through conflict, take responsibility without shame, and believe they’re worthy of love even when it’s hard.

Insecure Attachment

Insecure attachment develops when safety and connection were inconsistent. The nervous system adapted for self-protection, which shows up as one of three patterns: some by clinging (anxious attachment), some through distance (avoidant attachment), and some by doing both (disorganized attachment.)

Object Constancy

Object constancy is developed in infancy and it helps us feel a secure sense of connection even when the other person is not physically or emotionally present. When it’s solid, a person can comfortably tolerate distance, conflict, or ambiguity. But if we experience trauma, neglect, or inconsistent caregiving in infancy, it can disrupt that development.

For someone who is anxious with low object constancy, distance can feel like disconnection or being forgotten, and conflict or even healthy boundaries can feel like rejection, creating panic. For someone who is avoidant, connection cannot be trusted, and may feel uncomfortable or even smothering, causing them to want emotional or physical distance. For someone who is disorganized, they never knew what to expect, and will flip flop between pulling you close and pushing you away.

We all have strategies that once kept us safe. The goal is to recognize them, understand where they came from, and choose something truer when it’s safe enough to do so.