The Nervous System

The nervous system is the body’s threat-detection and response system, and in relationships, it is almost always the system in charge.

This page is not about your history, your attachment style, or what you should do differently in relationships. It’s about the system underneath all of that, your Nervous System.

Specifically, it’s about how the nervous system operates in relational contexts, how it determines what feels safe or threatening, and how it mobilizes your body long before thought, intention, or insight come online. This system isn’t tracking meaning, fairness, or long-term consequences. It doesn’t care about happiness or inner peace. All it cares about safety, whether physical, psychological, or emotional. Its only job is to look for threats, evaluate risk, and move you to safety by any means necessary.

.

Nervous System 101

Your nervous system is the system that keeps you alive. It has several branches that do different things like breathing, making your heart beat, digestion, etc. The Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) is the branch that manages how we relate to ourself and others. It’s the branch that manages the bulk of our thoughts, beliefs, and behaviors in any interpersonal relationship, especially romantic ones. On this page and throughout UNRAVEL, when you see ‘nervous system,’ it is referring specifically to this branch, the SNS.

Your nervous system’s job is to constantly assess safety and danger and prepare your body to respond. If it detects a threat, whether real or perceived, it shifts you into action to keep you safe. It’s making these assessments all the time, in every situation, whether you realize it or not.

Most of this process is automatic. You don’t get to decide what feels safe or threatening. You can’t consciously turn the system on or off. Your nervous system is always scanning your environment and your relationships, looking for cues that signal connection, risk, pain, loss, or instability. This happens very quickly. Your nervous system will assess a situation and activate your reaction in milliseconds.

A big part of how it does this is by shifting what’s called your state. State is the mode your system is operating in at a given moment. It’s the baseline that every experience is filtered through. Calm. Anxious. Defensive. Overwhelmed. Shut down. These aren’t moods or feelings, they’re whole-body conditions that affect how you think, feel, and react.

How the Nervous System Is Calibrated

When you’re born, your nervous system is largely a blank slate. It gets calibrated over the first several years of life to form a foundational blueprint for connection, love, and relationships, based on repeated experience.

As a child, your system is learning one core thing: what it takes to stay connected to the people you depend on. Who shows up. Who doesn’t. What closeness feels like. What conflict leads to. Whether care is predictable, conditional, overwhelming, absent, or unsafe. This learning happens long before language or conscious memory. Your body assumes instinctually from birth that the person(s) you depend on for food, shelter, and survival love you. They draw the blueprint.

Unfortunately, we do not get to choose who draws our nervous system blueprint. Some caregivers are loving and affectionate while others are neglectful or cause fear. If you’re life circumstances were chaotic and unstable, that also goes into the blueprint. Your nervous system adapts to whatever reality it’s in, and assumes that this is what love and safety is supposed to be.

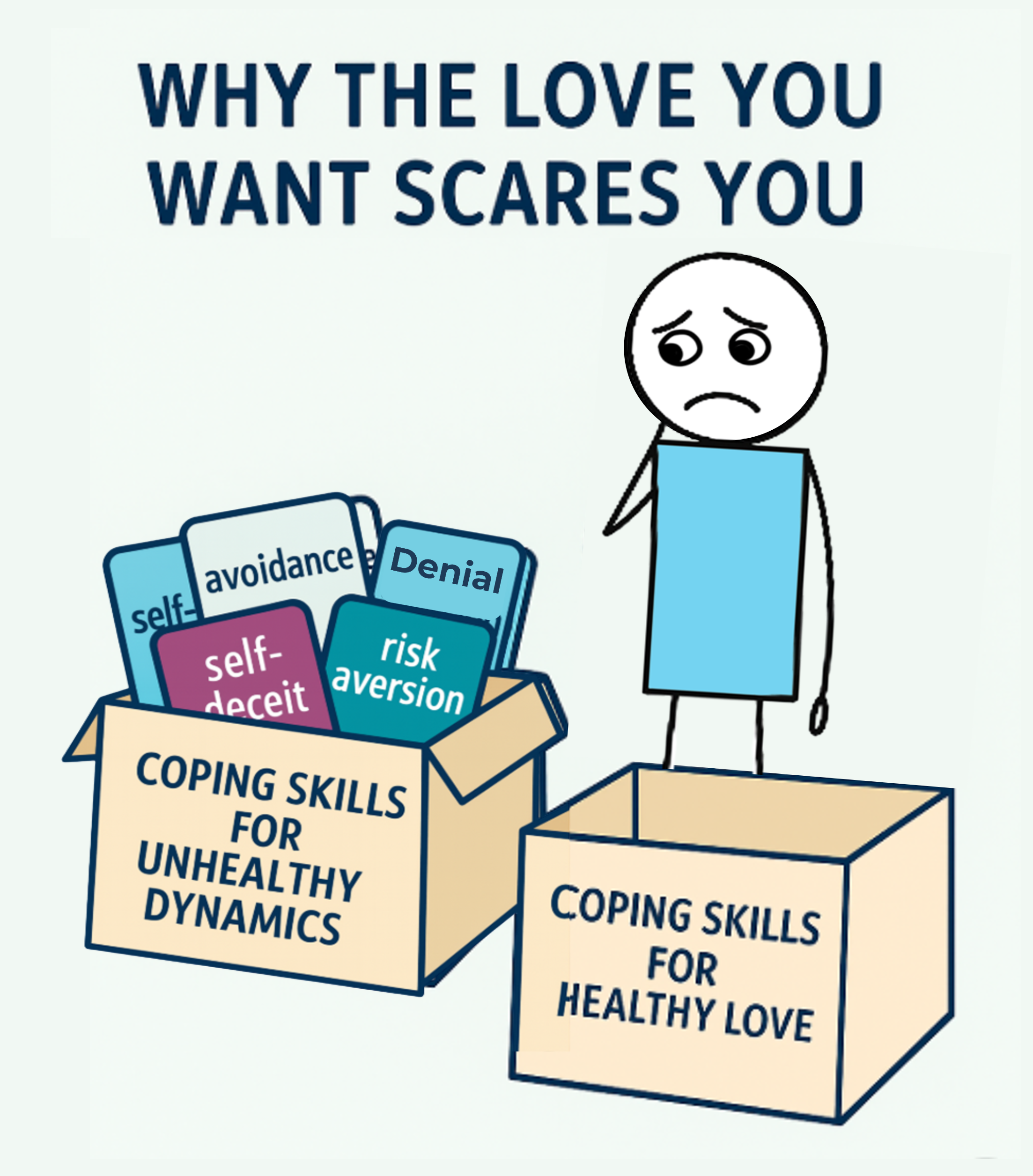

Maybe love was inconsistent. Maybe your parent was smothering. Maybe shame was used to teach right and wrong. If being ‘good’ and feeling loved was tied to pleasing, staying quiet, or being useful, you adapted to become those things, and they became your requisites for love. You learned to do whatever you had to do to feel safe in a life you had little control over. Staying out of sight, parenting your own parent, ignoring your needs, being easy and agreeable—these became your coping skills to survive your environment.

These coping skills are not objectively bad or problematic. They helped you psychologically survive harmful circumstances. The problem is that as those circumstances change, they don’t automatically update. When you become an adult, you are no longer dependent any one person for survival in the same way. You can leave unsafe situations.* You can choose who stays in your life. But your nervous system doesn’t know that.

Once the core blueprint is formed, those coping skills become your toolbox to navigate relationships, and you continue using those tools in situations where they no longer serve a purpose. As a child, they were defenses to protect you from the people you needed connection and love from.

As an adult, you shouldn’t need to protect yourself from people you love and have connection with, but if that’s how your nervous system learned to manage connection, that’s what it will do. And if you’re staying small, being responsible for others’ emotions, ignoring your needs, and being easy and agreeable as an adult, you’re likely to end up in unhealthy relationships

How it Decides What’s Safe and What’s Not

You carry that blueprint with you for life, and your nervous system uses it constantly. Not thoughtfully. Not carefully. Constantly. You do not do this consciously and you do not have a say in it. It happens at the nervous system level and triggers a response almost instantly, based on the blueprint of how it managed similar situations.

Your nervous system wants to know if this is familiar, if it matches the blueprint. If so, it goes to the toolbox to grab the appropriate tool according to the now decades old blueprint. It’s essentially looking for a similar experience in your past to see how it should respond. Does this feel familiar? Does this resemble something that once led to closeness, rejection, conflict, or loss?

This is where things start to go wrong.

Your nervous system doesn’t ask whether the current situation is healthy, fair, or good for you long term. It asks whether it matches something it already knows how to survive. If so, it thinks, “The blueprint says ‘We know this, we have a tool for it, let’s use it,’” and it activates the old coping skills. This entire process happens automatically and outside of conscious awareness.

his is how coping skills that once kept you safe turn into defense mechanisms that still feel protective, but now actively cause harm to you and the people around you. They create a sense of safety and stability, but they’re not real, and often come at a high price.

If, however, there is nothing like this on the blueprint, no tool for this in the toolbox, the nervous system considers it unfamiliar. It doesn’t know what this is, what to expect, how to navigate it, and how keep itself safe. Rather than chance it, your nervous system tends to rule it as potentially dangerous and sound the alarm. Uncertainty and ambiguity can feel especially threatening because the system can’t predict the outcome.

An unfamiliar situation isn’t necessarily dangerous, but it’s not guaranteed to be safe either. If it is objectively safe, meaning the situation doesn’t actually pose a threat, but the nervous system is treating it that way, it’s called a perceived threat. No real threat exists, but if it’s unfamiliar, it will likely create discomfort or fear anyway.

In that case, your nervous system isn’t responding to objective reality. It’s responding to how the present moment lines up with your blueprint and your earliest experiences. That’s why reactions can feel confusing or disproportionate later. You weren’t responding to what was actually happening. You were responding to what your nervous system expected to happen.

This process happens quickly, quietly, relentlessly, and often destructively. Unfortunately, the nervous system doesn’t explain itself. It just needs you to act.

How Our Nervous System (Mis)Communicates

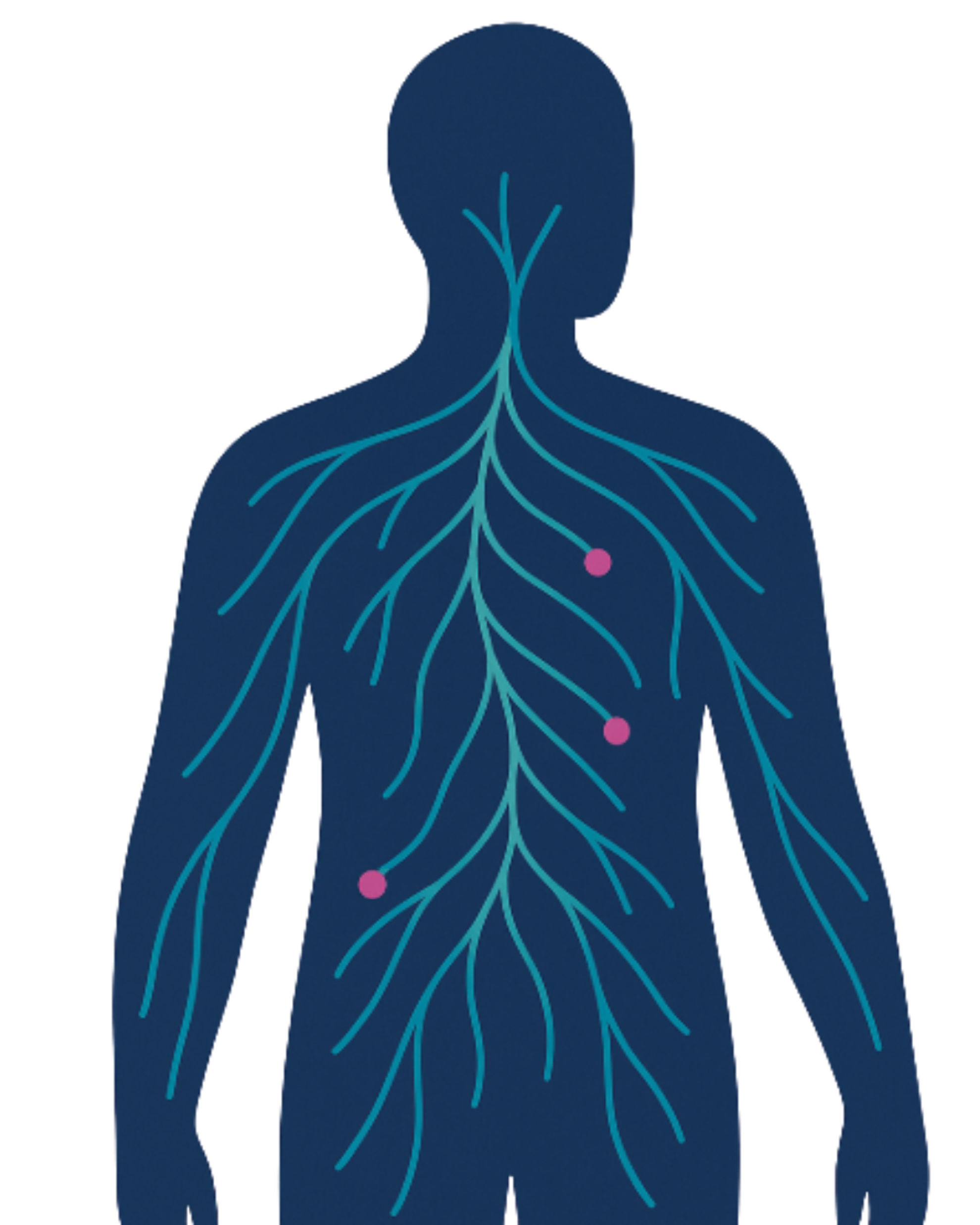

Once your nervous system decides something feels unsafe, it needs you to act. Fast. It doesn’t have the luxury of explaining why, giving you context, weighing nuance, or walking you through its logic.

Your nervous system and your conscious mind are not equal partners. The nervous system makes the call, and it doesn’t trust your conscious mind to act fast enough or follow directions. When it believes safety is at stake, it will bypass your thinking and tell you what you need to hear to get you to comply. Instead of explaining what it’s reacting to, it delivers conclusions.

Instead of saying “This feels unsafe, it’s not familiar, I don’t have a tool for this,” it will say things like:

“I’m not good enough.”

“They’re pulling away.”

“They deserve better.”

“I’ll only hurt them.”

“They’re better off without me.”

“I can’t fix this.”

“It’s too late.”

And the worst part is that you will wholeheartedly believe them.

Your nervous system knows these are incredibly effective. Especially since your it may been telling you these things your whole life. Your early relationships probably taught you things like having needs is selfish, your feelings don’t matter, your pain isn’t important, etc. Those experiences make it really easy to believe when your nervous system later tells you you don’t deserve good things or you’re not worth being chosen.

So they feel like facts. They come with emotional intensity and a sense of certainty that’s hard to shake. Your nervous system doesn’t care if you’re happy. It doesn’t care about inner peace. All it cares about is safety, and it needs you to believe the message so you’ll push away what it has deemed a threat, no matter how safe it actually is.

Sadly, logic rarely helps. You can know, intellectually, that this person genuinely loves you or that it’s ok to choose yourself. You can know you’re not being forgotten or replaced. But feeling isn’t the same as knowing, and feelings run the show.

This miscommunication is one of the main reasons relationships become so painful. You’re not reacting to your current situation. You’re reacting to an outdated alarm system and a faulty autopilot