I Want To Understand My Own Patterns

Why You Do What You Do

Your behavior isn’t random, and it isn’t a personality flaw. It’s the fallout of years of learning what connection costs and what you have to do to survive it.

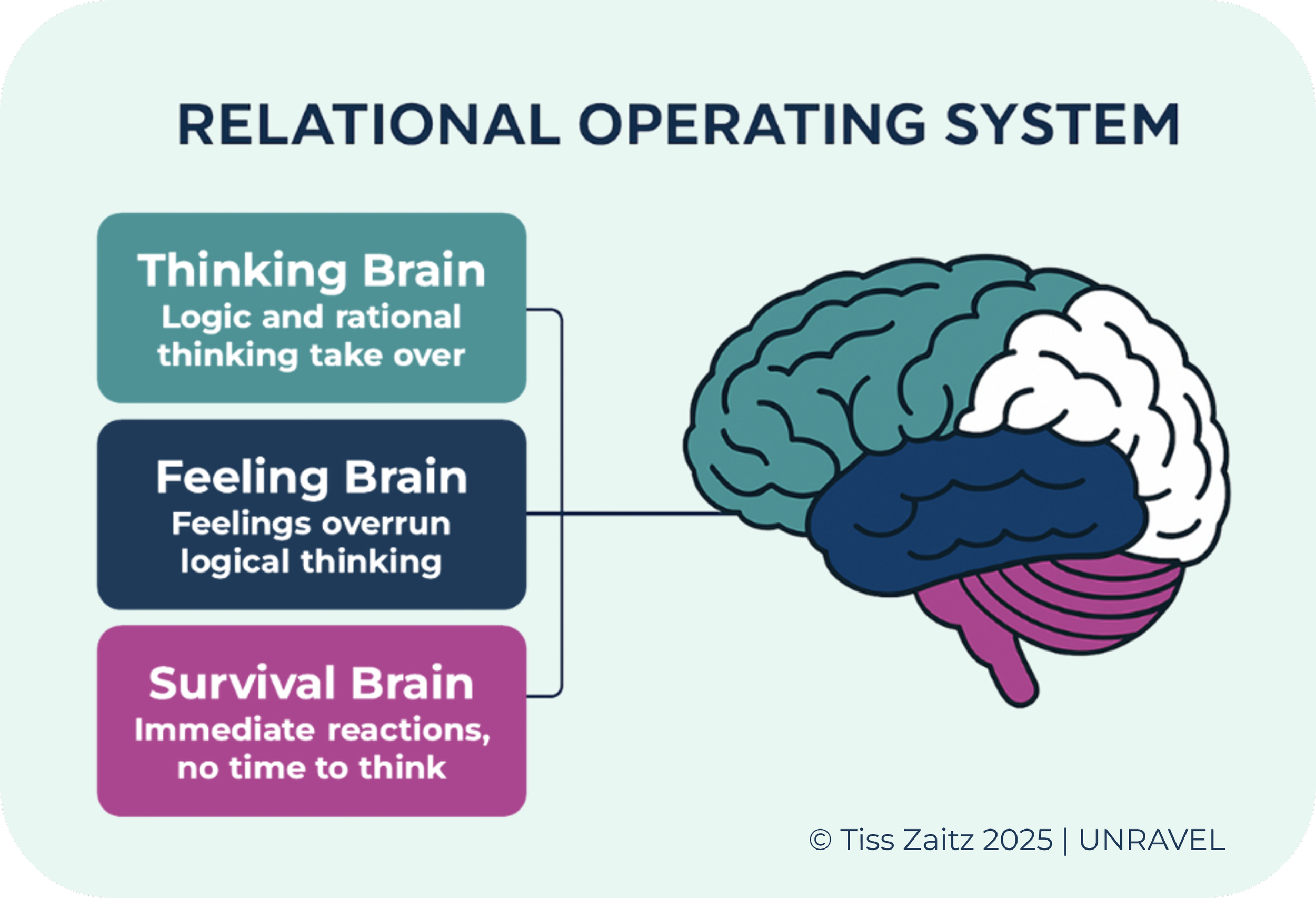

Whatever you default to now, whether it’s shut down, chase, overthink, people please, deflect, withdraw, pick fights, or avoid conflict, didn’t come out of nowhere. It came from a nervous system that was trained long before you had any real say in the matter. Your Survival Brain wrote the script, your Emotional Brain reinforced it, and your Thinking Brain usually shows up late, trying to make sense of the mess (though sometimes it doesn’t show up at all.)

If you grew up with unpredictability or rejection, inconsistency feels normal, and distancing feels safe. If you grew up earning approval, you still live by earning it. You’re not weak or dramatic; you’re conditioned with patterns. And patterns don’t care about your intentions; they run automatically without you even realizing it.

This journey isn’t about blaming your past or excusing your present. It’s about understanding that your Relational Operating System is still running old code, and old code doesn’t delete itself just because now you know better. You react the way you do because it once protected you, and if you want to change, your autopilot needs to be retrained.

Once you can see the psychological logic underneath your behavior, you finally have leverage against your own system and can start choosing instead of just reacting. And that’s the moment things actually change.

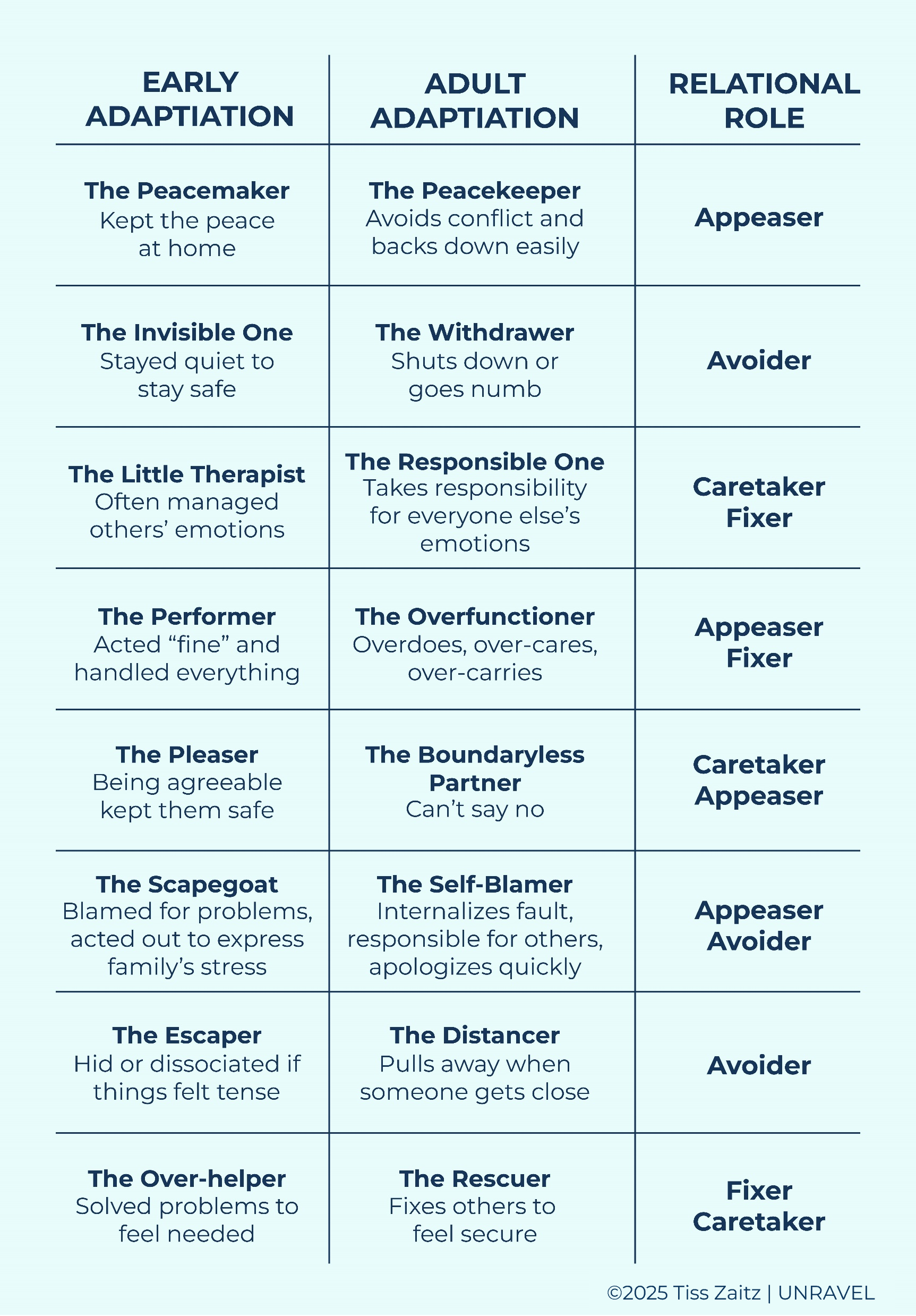

Your Old Survival Strategies

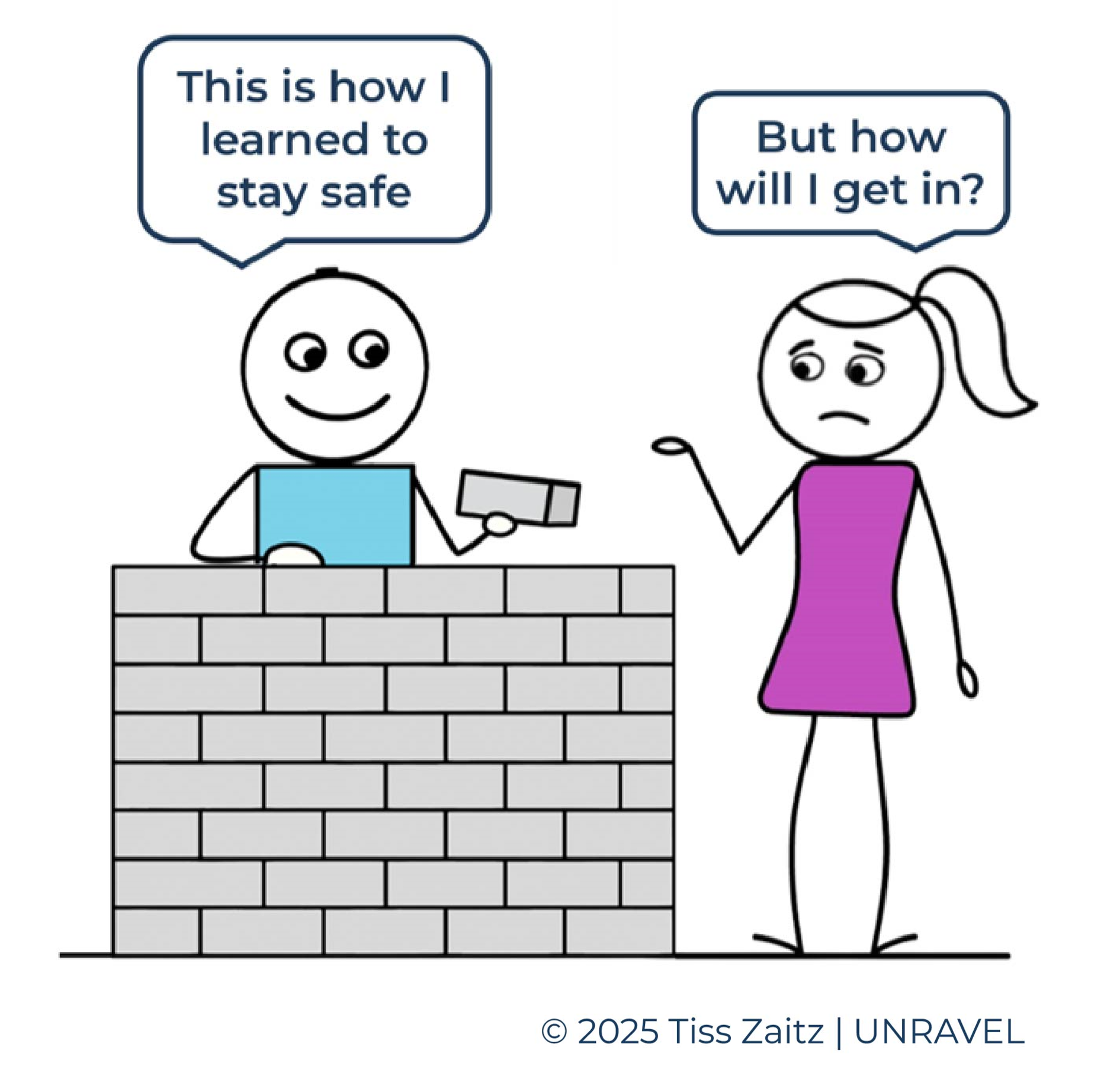

Most of what you do in relationships isn’t driven by conscious choice, it’s driven by what kept you safest when you were young. These strategies weren’t unhealthy at the time. They kept you out of trouble, maintained peace, preserved the connection, and made you feel seen instead of invisible. You did whatever kept the people around you happy so they wouldn’t respond to you in ways that made you feel unsafe.

The problem is your nervous system doesn’t update itself just because you grew up and your life changed. It keeps using the same moves long after they’ve stopped being useful.

When something signals fear or danger, whether it is real or perceived, your Survival Brain reacts first, your Feeling Brain amplifies the signal, and your Thinking Brain tries to sort it out. So when you shut down, overthink, fix, chase, overexplain, or avoid, you’re not actively choosing those behaviors. You’re defaulting to the self-protective autopilot strategy your system still thinks you need.

For some people, that means distancing or disappearing emotionally. For others, it means leaning in harder, explaining more, giving more, or trying to control what feels unpredictable.

These behaviors differ greatly and show up in numerous forms, but they all stem from the same place: fear. Fear of losing connection, fear of being disappointed, fear of conflict, fear of abandonment, fear of repeating something you promised yourself you’d never go through again.

Old survival strategies don’t disappear with age or insight. You don’t outgrow them. You have to be able to recognize them, then retrain your nervous system. Neither is easy. But once you can see your patterns clearly, you’re finally in a position to do something different.

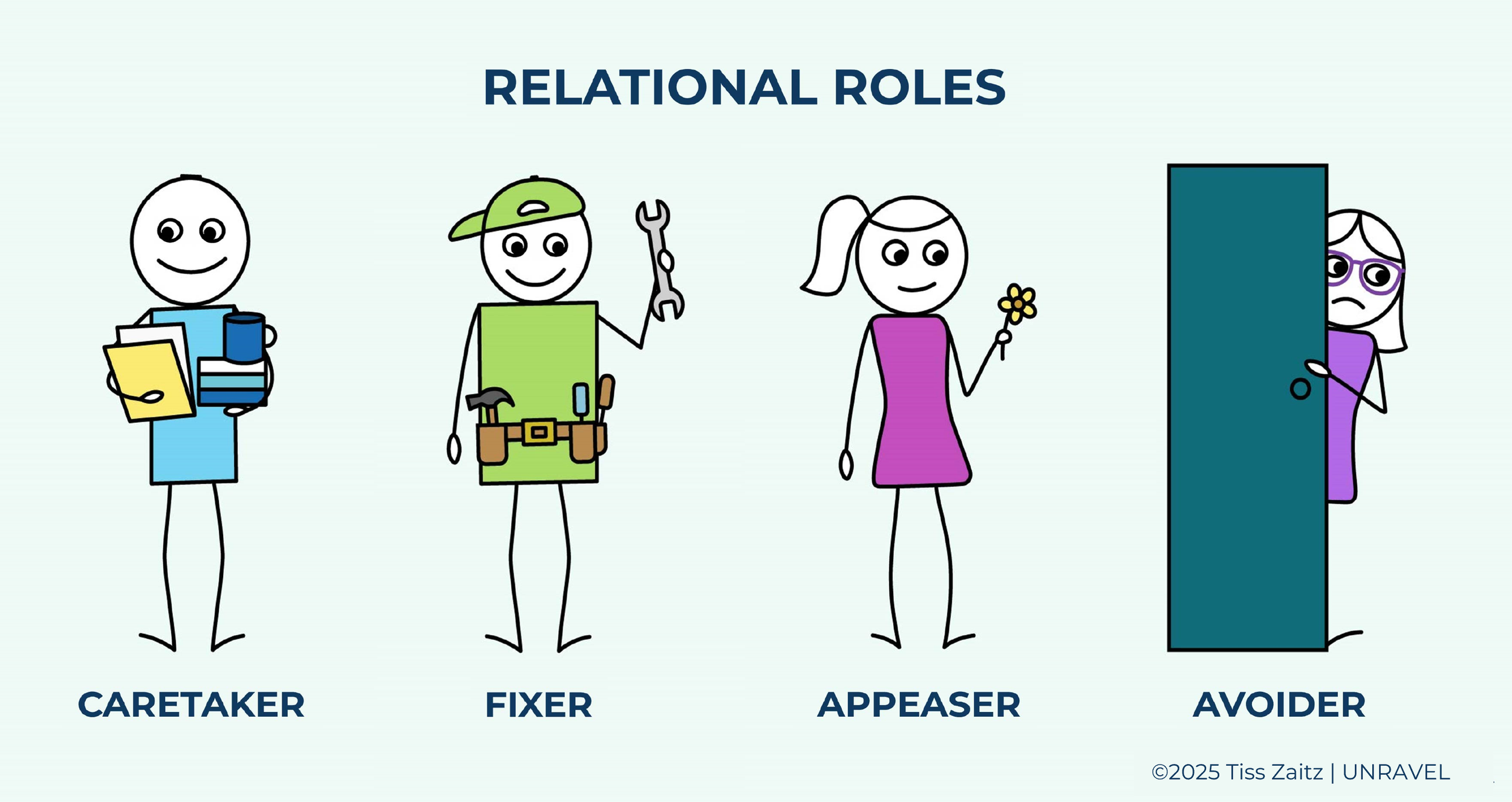

The Roles You Take On

Everyone has a role they slip into when things feel tense, uncertain, or emotionally risky. You didn’t choose these roles. You learned them. Maybe you learned to be the Caretaker, carrying everyone else’s needs before your own. If you had to patch every crack before it got worse, you may have become the Fixer. You may have taken on the role of the Appeaser, smothering conflict before it had a chance to land. Or maybe you pulled away, stayed quiet, and took up as little space as possible, becoming the Avoider and keeping your distance in order to stay safe.

These roles are not static and often overlap. They can play out differently based on an individual’s circumstances and resources, leading to numerous adaptations and combinations.

Some people over-function while others may under-function. Some perform being “fine” whether they are or not, or are not reactive, as if nothing gets to them. (This may seem easy going, but it’s actually quite unhealthy.) Some people sacrifice their own needs to cater to others’. These aren’t personality traits. They’re roles your nervous system built to survive your early environment, and until it learns differently, they’re the roles that will shape your relationships in adulthood.

When your Survival Brain detects even a hint of emotional threat, it pushes you straight back into your earliest position. You might feel yourself shifting before you’ve even registered what happened. Your posture changes. Your tone tightens. Your priorities shift toward whatever version of “safer” your nervous system recognizes.

The Feeling Brain amplifies the fear, and emotions take over. Your Thinking Brain usually arrives after the fact, trying to explain why you did something that doesn’t match who you want to be.

Roles are predictable because they’re familiar. They feel automatic because they’re the mechanisms you’ve been using your whole life to feel safe and in control; they’re ingrained in your nervous system. Seeing them play out in your life and recognizing them for what they are can be difficult and confusing, but if you can’t see them, they’ll end up running your relationships for you.

Recognizing your role isn’t about diagnosing yourself. It’s about understanding what role you default to when fear takes the wheel, and deciding whether that version of you is still worth protecting.

The Stories That Drive Your Behavior

Your behavior isn’t just shaped by your nervous system. It’s shaped by the story your nervous system believes. Every survival strategy is held in place by a narrative you learned before you even knew what a narrative was. These stories sound simple on the surface but run deep.

They can sound like:

“If I ask for too much, I’ll lose them.”

“If I don’t take care of everything, everything falls apart.”

“If someone pulls away, it’s because I did something wrong.”

“If I relax, the other shoe will drop.”You don’t repeat these stories because they’re true. You stay in them them because they once protected you from pain you weren’t prepared to handle.

Once a story gets installed, your Relational Operating System starts filtering your thoughts and experiences through it. The Survival Brain reacts to the story as if it’s fact. The Feeling Brain adds urgency and emotion, which often drives your behavior. And the Thinking Brain arrives later, trying to make sense of why a small moment hit you like it did.

You read into tone, hesitate to set boundaries, panic when someone gets quiet, overanalyze texts, or assume you’re being rejected when nothing is actually happening. The behavior makes perfect sense once you see the belief underneath it.

These stories won’t go away on their own. They feel like instincts, which means they feel extremely real, but they’re not. They’re rehearsed scripts your system keeps replaying.

When you finally name the story driving your behavior, the behavior stops feeling inevitable. You can question it. You can challenge it. You can replace it. And you can stop acting out of an outdated version of who you once had to be.

Here are 6 Situation Cards, each showing the common conditioned responses to a given situation and some healthier alternative responses you could try instead. Use the sliders below to see toggle between the two.

These conditioned responses aren’t flaws. They’re habits you learned to survive environments that didn’t give you better options. Now you have better options.

Behavior You Think Is Normal, But Isn’t

Most people don’t recognize their own unhealthy behavior because it feels familiar. You call it “just how I am,” or “how relationships work,” or “what anyone would do.” It doesn’t occur to you that the things you’ve normalized were rooted in fear, not preference. When you grow up adapting to other people’s moods, chaos, silence, volatility, or inconsistency, your system quietly rewires itself. Overexplaining feels polite when it’s actually defensive. Overthinking feels responsible, but it’s rumination. People-pleasing seems kind even though it’s self erasure. Avoiding conflict sounds mature when it’s really dismissing an issue. Chasing someone who’s pulling away feels like showing interest or care, but it can be needy or overbearing. Anything that protected you once can start to feel like common sense.

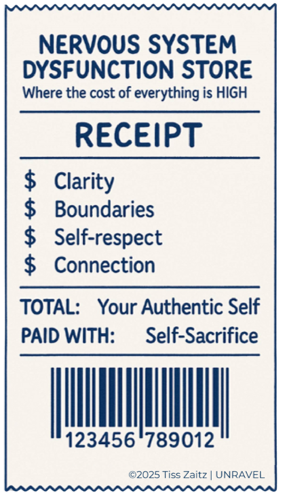

You don’t question these behaviors because they’ve always been there. They’re built into your Relational Operating System and your nervous system fires them before you even consider another option. You think you’re being thoughtful, flexible, easygoing, loyal, or resilient. What you’re actually being is patterned. Behaviors that cost you clarity, boundaries, self-respect, or emotional safety don’t magically become healthy just because you’ve lived with them for a long time.

This section isn’t about shaming yourself. It’s about calling things what they are. The moment you stop labeling survival behavior as “normal,” you get access to choices you never had. Recognizing the difference between what’s familiar and what’s healthy is the first step toward breaking the pattern instead of reinforcing it.

Behavior That You Think Protects You, But Actually Hurts You

Some of the most damaging things you do in relationships are the exact things that once kept you safe. Your system learned early how to dodge pain, manage fallout, and minimize risk. It doesn’t care that you’re older now or that your life is different. It still uses the same strategies because they worked then. Shutting down protected you from saying the wrong thing. People-pleasing protected you from someone’s anger. Chasing protected you from feeling discarded. Withdrawing protected you from being disappointed. Fixing protected you from feeling insignificant. These aren’t random reactions. They are the fastest route your nervous system knows away from danger.

The problem is that protection in the moment becomes damage over time. You avoid discomfort upfront, and then pay for it later. The shutdown keeps you from getting hurt but blocks intimacy. The people-pleasing keeps the peace but erases your needs. The chasing keeps someone close but pushes them further away. The withdrawal keeps you safe but leaves you alone. The fixing keeps you relevant but makes the relationship one-sided. The same strategies that shielded you from harm are now preventing you from getting the relationships you want.

You don’t need to throw these behaviors out. You need to understand why they activate and what they cost you. You don’t need protection from the people and experiences in your past, your experiences today are different. When you can see which of your patterns are actually self-preservation in disguise, you can decide when to use them and when to choose something better.

What Your Patterns Cost You

Patterns always have a price. They feel protective in the moment, but there’s always a bill waiting on the other side. You don’t notice it when you’re acting on instinct because the immediate payoff is relief. You calm the tension, avoid the conflict, or pull yourself out of the emotional line of fire. But the long-term cost is high. Every time you shut down instead of speaking, you lose clarity. Every time you people-please, you lose your boundaries. Every time you chase, you lose self-respect. But when you withdraw, you lose connection. And fixing drains energy you’ll never get back. The short-term comfort is real, but so is what you sacrifice for it.

Patterns don’t just shape your behavior. They shape your relationships. They determine who you choose, what you tolerate, how much you give, and where you shrink. They decide which needs you ignore, which red flags you override, and which parts of yourself you hide because they don’t feel “allowed.” They’re as much about what you lose as what you avoid facing. And the worst part is that the cost feels familiar, so it doesn’t even register as a cost. You just live with it because it matches the version of connection you learned to expect.

Seeing the cost of your patterns isn’t about blaming yourself. It’s about being honest. You can’t choose differently if you can’t see what repeating the same behavior is taking from you. When the price becomes too high, change stops feeling optional. It starts feeling obvious.

Seeing Yourself in Real Time

The hardest part of changing your patterns is noticing them while they’re happening. Not after the argument. Not after the overthinking marathon. In real time. Your Survival Brain moves fast, and your Thinking Brain doesn’t show up until the damage is halfway done. That means the moment you start shutting down, chasing, fixing, or pretending everything is fine, you usually don’t even know you’re doing it. You only feel the panic, urgency, irritation, or numbness that pushes you straight into the behavior. And it will feel right.

The process is not easy. Once you become aware that you have patterns, it takes time to catch yourself doing them. For some people, this is one of the most uncomfortable parts of healing. Being aware of behavior you’re not proud of while still doing it can be embarrassing or make you feel guilty. But your behavior isn’t suddenly worse, you’re not suddenly acting in ways you weren’t already acting before, it’s that now you’re able to see it. Ignorance may be bliss, but awareness, however uncomfortable, is the only way to make a change.

The key to remember is that this is a turning point. Awareness doesn’t stop the pattern immediately, but it gives you leverage. When you can identify your own role, strategy, or narrative in the moment, you’re no longer running on autopilot. You can pause. You can delay the reaction. You can choose a different next step. You can interrupt the sequence instead of surrendering to it. Real-time awareness is where choice actually begins.

Interrupting the Pattern

Interrupting a pattern isn’t about being calm, enlightened, or perfectly regulated. It’s about catching yourself early enough that you can choose something different before the spiral takes over. Patterns run on momentum. Once the shutdown, chasing, snapping, fixing, or people-pleasing starts rolling, it’s hard to stop. The goal isn’t to never react. It’s to create just enough space for a different move.

A pattern interruption is anything that breaks the automatic sequence. It doesn’t have to be dramatic. It can be a pause before you respond. A breath before you reply. Naming what you feel instead of acting on it, or asking a clarifying question instead of assuming the worst. Saying “I need a minute” instead of disappearing, or holding your boundary one more second than you usually do. These small actions don’t look powerful, but they disrupt the timeline your nervous system expects, and that’s what rewires the behavior.

This can be very difficult to do. You have to look for and be willing to admit that your behavior might be unhealthy, unfair, or even harmful. At first you’ll notice it after the fact. This is often the most uncomfortable part of the whole process. You now know that you behave in ways you may not be proud of, so you may feel guilty or embarrassed. After a while, you’ll start to catch it while it’s happening, sometimes in time to shift the behavior, other times not.

This process is not fast and it’s not linear. But in time, it gets easier. You’ll notice yourself over explaining, losing your temper, saying ‘yes’ or ‘maybe’ when you want to say ‘no’, or pulling away. As as the awareness sharpens, you’ll start noticing the urge to do those things, but choosing a different reaction instead.

Interruptions feel uncomfortable because they go against your instincts, against everything your system has been trained to do. Your Survival Brain wants speed. Your Feeling Brain wants emotional relief. Your Thinking Brain wants accuracy. An interruption slows all of that down long enough for you to get your hands on the wheel. You don’t fix the pattern in one move. You break it one micro-choice at a time. And every interruption is proof that you’re not as stuck as you feel.

Why Change Feels So Hard

Your nervous system isn’t built for change. It’s built for survival. And survival isn’t about what feels good, it’s about what feels predictable. Even when a situation is painful, if you’ve been through something similar before, your system prefers it over the uncertainty of something new. We simply are not wired to be comfortable with uncertainty. Familiar harm feels safer than unfamiliar possibility.

Change doesn’t just ask you to do something different. It asks you to lose something. A role. A routine. A relationship. A fantasy. A version of yourself you’ve been carrying for years. Loss feels immediate and concrete. The benefits of change feel hypothetical, and your brain will always choose the thing it can measure over the thing it can’t.

There’s also the fear of being wrong. People will stay in situations that hurt because the idea of regretting a choice feels more terrifying than the discomfort they already know how to navigate. Hope becomes a coping strategy. “Maybe it’ll get better” is the emotional discount code your system uses to avoid disruption.

You may talk about leaving a toxic job for years but never do it, because what if the next job is worse? At least in this job you know how to navigate the personalities and culture to stay relatively safe, and it has good salary and benefits. It’s predictable. No matter how much the status quo is hurting you, not knowing the outcome of changing holds you back.

Relationships work the same way. You might not be happy, but there’s no guarantee leaving will make you happy either, and leaving requires painful changes. You have to give up a lot of things you don’t want to lose without knowing if you’ll find them with someone else, and you know how to manage things in your current relationship. So you stay where you’re not happy because it’s predictable.

If your early wiring paired closeness with chaos or inconsistency, change can feel even more dangerous. Stability — even painful stability — feels like safety. Letting go threatens the fragile equilibrium you’ve built, and your system will protect that before it protects your happiness.

Change also disrupts identity. Patterns become part of who you think you are. Roles solidify. Rewriting them can feel like stepping into a version of yourself you don’t fully recognize. And the moment you see something clearly, you also have to admit what wasn’t working before — and that creates dissonance your ego would rather avoid.

None of this means you’re incapable of changing. It means your system is trying to keep you safe in the only way it knows how: by sticking with the familiar. Resistance isn’t proof that change is wrong — it’s proof that change is happening.

The Hidden Costs of Not Changing

Change feels risky because it asks you to step into uncertainty. But staying where you are isn’t neutral. The idea that doing nothing prevents harm or that waiting doesn’t have consequences is misleading. Not changing keeps both of you in something that may not be working, even if the love is there and neither is actively causing harm.

Not changing requires sacrifices, too. It just hides the cost better.

When you remain in a pattern that isn’t working, you still have to adapt. You may start editing your needs to avoid conflict without even realizing it. Maybe you swallow resentment and tell yourself it’s patience. You might minimize parts of yourself to keep the peace, or quietly carry anger toward someone who hasn’t technically done anything wrong. Over time, you are sacrificing parts of yourself, which chips away at your self-worth. You’re not just staying in the same place, you’re slowly reshaping yourself to make that place tolerable. And that is rarely one sided. Your partner may be doing the same.

We also tend to misjudge the math. The fear of changing is vivid and immediate, so your mind fills in worst-case scenarios and treats them as likely. The potential benefits, on the other hand, feel abstract and uncertain, so they’re discounted. You overestimate how much changing could hurt you and underestimate how much staying already is. You feel stable because it’s familiar and comfortable, but you’re living in a house of cards.

Not changing doesn’t spare you loss. It just spreads it out over time, and you can’t get that time back. Clarity erodes. Energy drains. Self-trust weakens. And eventually, you may look around and realize you’ve been paying with parts of yourself you never meant to give up. In the end, trying to spare yourself and your partner short-term pain can create far more damage over time. People often still face the same ending, just months or years later. The short-term pain you wanted to avoid then comes in addition to the long-term damage of staying.

People often spend years tolerating long-term unhappiness to avoid shorter, temporary pain and uncertainty.

This isn’t about forcing a decision or pushing yourself to act before you’re ready. It’s about seeing that inaction is not consequence free, and the consequences of staying are often more harmful to both partners. Once that becomes clear, the question shifts from “Why is this so hard?” to “What am I willing to keep paying for?”

Choosing Behaviors That Are Uncomfortable but Healthy

Healthy behavior doesn’t feel natural at first. It feels wrong. It feels risky. It feels like you’re breaking some unspoken rule you’ve lived by for years. That’s because your system isn’t calibrated to safety. It’s calibrated to familiarity. When you start choosing behaviors that don’t match your old patterns, your nervous system reacts as if you’re doing something dangerous. Setting a boundary feels harsh. Asking for clarity feels needy. Saying no feels selfish. Slowing down feels uninterested. Staying present feels exposed. Of course it feels uncomfortable. You’re disrupting the patterns that protected you.

Choosing healthier behavior isn’t about feeling brave or confident. It’s about tolerating the discomfort long enough for your system to learn that nothing bad actually happens. Your Survival Brain protests. The Feeling Brain gets loud. The Thinking Brain has to stay steady anyway. You don’t wait for comfort before you change. Comfort comes after the pattern breaks, not before.

Healthy behavior gets easier, but only after repetition. Boundaries stop feeling confrontational. Honesty stops feeling dangerous. Pulling back from fixing stops feeling like abandonment. Staying open stops feeling like a trap. You can’t think your way into healthier patterns. You have to live your way into them, one uncomfortable choice at a time. That’s how your system learns a new story about what safety actually feels like.

You don’t have to have the answers yet. Being here at all means you’ve stopped pretending everything is fine, and that’s a bigger step than most people ever take.

Seeing the truth is painful and disorienting, but it’s also the moment your life starts shifting. You’re facing the thing you were afraid to look at, and that takes real courage.

Even if you’re not ready to act, you’re already moving. You’re already changing. And that matters.

Before you go…

I sincerely hope this journey gave you something valuable: clarity, comfort, validation, maybe even a little relief from the confusion. If you’re feeling overwhelmed, raw, or unsure what comes next, that’s okay. You’re doing hard things. Really hard things.

If and when you want to keep going, UNRAVEL has more to offer. The Foundations are the building blocks, they explain the underlying mechanics of relationship behavior. The Models & Frameworks show how those mechanics create and reinforce the patterns people get stuck in.

The information is in a slightly more academic tone, as these pages take on a more educational perspective…but still in clear, relatable language. You won’t find any 7 syllable words or sciencey jargon here.

I’d also love to hear your story. If you feel like sharing, you’re more than welcome to do so here. Your experience matters.

Thank you for trusting me to guide you. I wish you a lifetime of healthier, happier relationships.

Every relationship is unique, and emotional harm doesn’t always follow the same patterns. What you’ve read here reflects common dynamics, but it’s not a diagnosis. I hope something resonated, but please know this isn’t therapy or psychological, medical, or legal advice. It’s here to offer clarity, not conclusions.